NARRATIVE POWER ALLIANCE: EXHIBITION

January 9 – February 16, 2025

Venue: Barın Han, Istanbul

Boyacı Ahmet St. No:4, 34122 Fatih/Istanbul

Artists: Trans Memory Collective, Fatma Belkıs, Gregg Bordowitz, Nejbir Erkol, Kiki ggNash, Marina Papazyan, Zeyno Pekünlü, Belit Sağ, Jilet Sebahat, Üzüm Derin Solak, Serdar Soydan, Furkan Öztekin (with Ceyhan Fırat), Cansu Yıldıran

The Alliance of Narrative Power: Research Association for Democracy, Peace and Alternative Politics (DEMOS), Havle Women’s Association, Political Well-Being Platform, Positive Solidarity, KuirGaming, Social Policy, Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Studies Association (SPoD),

Van Star Women Association

Curators: Onur Karaoğlu & Alper Turan

Project Coordinator: Berfin Atlı (SPoD)

Initiated as a collective process by the Narrative Power Alliance—an assembly of diverse advocacy groups, platforms, and associations operating across Turkey—this exhibition arises from a shared mission: to understand, analyze, and seek new ways of contending with the rising anti-gender movements in the country. Drawing from the ongoing efforts of these organizations, the exhibition features new productions by Belit Sağ, Cansu Yıldıran, Fatma Belkıs, Furkan Öztekin (with Ceyhan Fırat), Kiki ggNash, Nejbir Erkol, Üzüm Derin Solak, and Zeyno Pekünlü, all aiming to unpack oppressive and homogenizing rhetoric. Through various media—painting, photography, video, publications, and installations—the artists explore the spaces between text, image, and body, reimagining the possibilities of collective subjectivity. In doing so, they construct alternative, liberating narratives and contribute to forming a counter-public. The exhibition also includes new texts by Marina Papazyan and Jilet Sebahat, archival research materials by Serdar Soydan and an existing work by Gregg Bordowitz, a selection from Dön-Dün Bak: The History of the Trans Movement in Turkey, an exhibition that was forcibly shut down by the Turkish government in July, 2024. In the face of potential closure, Narrative Power Alliance: Exhibition calls upon all art spaces in Istanbul to stand ready to host any part of this show. Curated by Onur Karaoğlu and Alper Turan, and coordinated by Berfin Atlı, the exhibition opens on January 9 and can be visited at Barın Han in Istanbul until February 16.

Under the weight of state and societal antagonism, public space collapses into a flattened terrain—pressing queer, trans, and feminist bodies out. Conceptually, the exhibition is situated along a tense line between forms of “oppression” (baskı in Turkish, also meaning “print/press”) and printed and pressed materials. The exhibition turns to the very act of pressing and embodying this pressure—a method of inscription and a violent compression of suppressed voices and embodiments subjugated to the surface. The works in this show channel their energy into printed, imprinted, pressing, and pressured matter. On flat surfaces -screens, paper, photographs, canvas, and walls- they carve out layered topographies that resist one-dimensional narratives, reasserting depth through narrative power. Every work in the exhibition acts as a body in a public space, coming together side by side for collective action.

Reading Differently, Writing Differently

Zeyno Pekünlü, Nejbir Erkol, Fatma Belkıs, and Gregg Bordowitz explore where and how out-of-margin narratives can be read and written, and how one can attain the poetics of error, malfunction, trivial, and what lingers at the edge of a page. Zeyno Pekünlü examines the reflections of collective emotions, strategy discussions, and highlighted points in the doodles collected from the Alliance’s meeting notes. Nejbir Erkol spreads the word “malfunction” (arıza) across the space to expose the tension between malfunction and consent (rıza). Fatma Belkıs retreats into the assumedly unread format of a brochure to write a woman’s self-defense story. Gregg Bordowitz brings the ongoing urgency of the AIDS crisis to the surface with a grammatically incorrect banner.

Images of We Were Here, We Are Here, We Will Be Here

At the core of this exhibition is a desire to visualize, document, and embody our existence while in defiance of censorship and erasure. Cansu Yıldıran, Belit Sağ, and Üzüm Derin Solak reimagine how we see and are seen, and how much we can show, through feminist, trans, Muslim, and Kurdish experiences. In her fragmented portraits created in collaboration with members of the Havle Women’s Association, Cansu Yıldıran discusses the ethics of the visibility of feminist Muslim bodies. With the films she produced with Ruken Ay from the Van Star Women Association and artist Sevil Tunaboylu, Belit Sağ focuses on the image politics of censorship. Üzüm Derin Solak investigates the possibilities of capturing an iconic photo in Istanbul’s public space that is simultaneously both women+ and queer following the withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention.

Archives of the Selves

By painting different versions of herselves, Kiki ggNash creates a self-appointed “family” portrait, embedding inaccessible past versions into visual memory through portraits on burned surfaces. In his installation, Furkan Öztekin revisits the ongoing collaboration with the late Ceyhan Fırat and earlier works derived from Fırat’s archive and corpus, thereby questioning the fluidity and reliability of these narrative constructions. Through archival archeology,

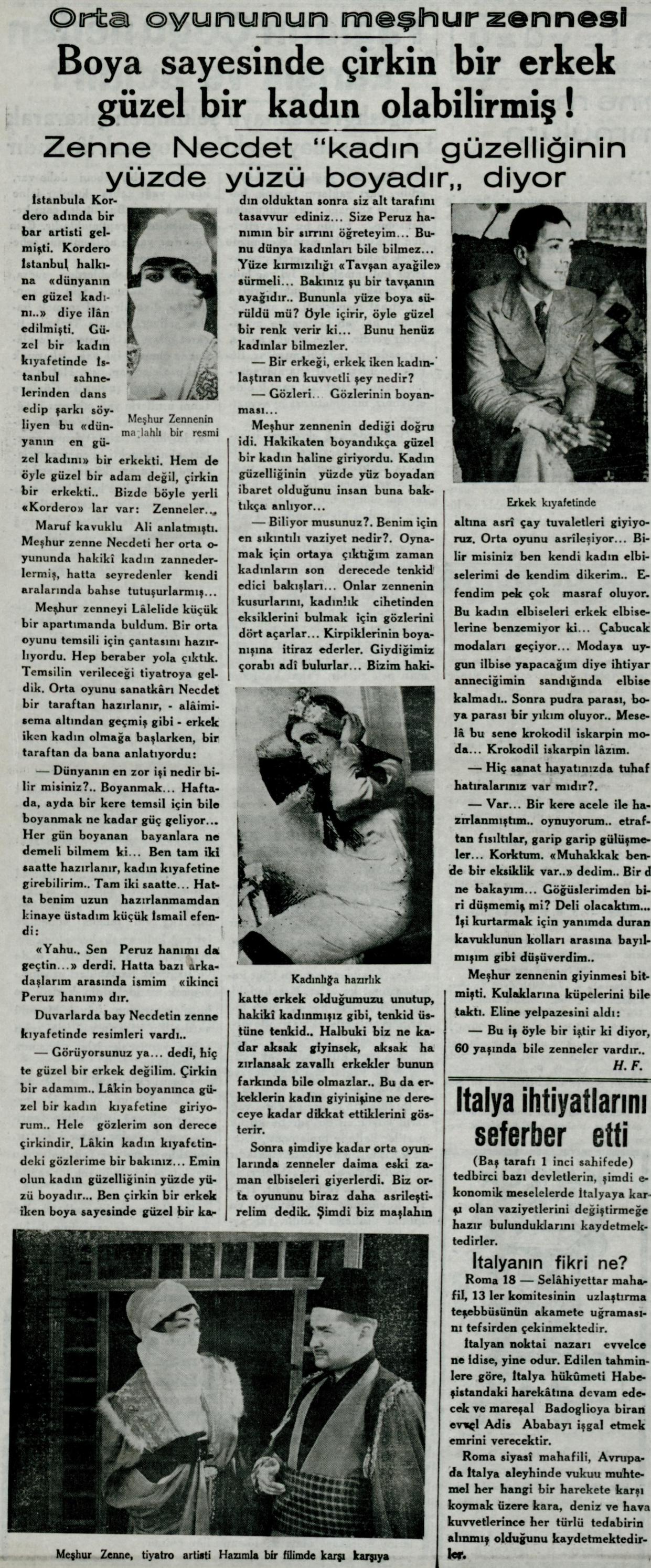

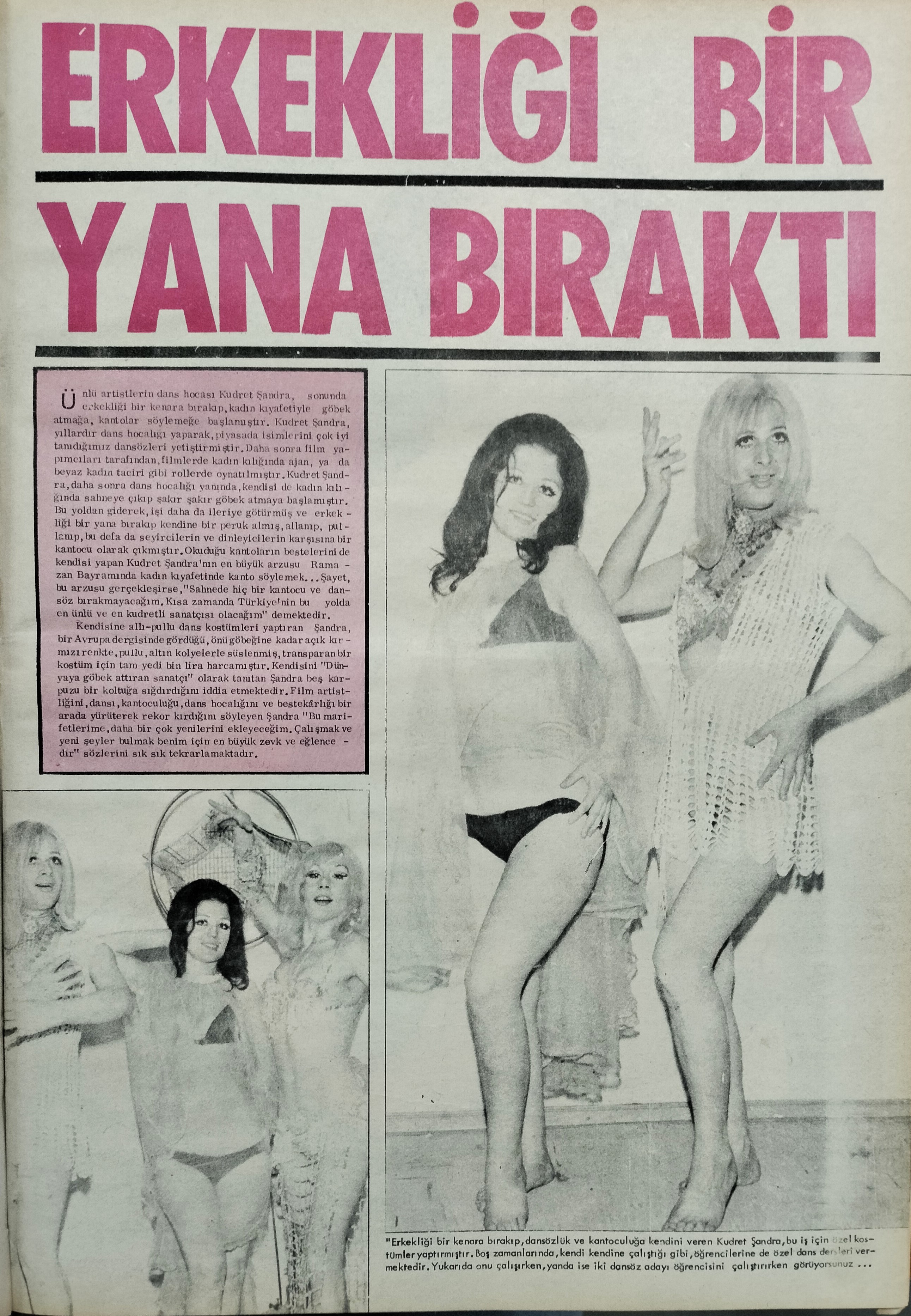

Serdar Soydan excavates the personal histories of gender-bending figures like Adnan Pekak, Kudret Şandra, and Zenne Necdet, constructed by media narratives. Marina Papazyan, in their fictional text, questions the impact of late Ottoman ethno-nationalist structures and gender codes on today's queer culture. Returning to Ülker Street, Jilet Sebahat offers a lament and testimony to the past and present of systematic violence against trans existence, thereby creating a contested geography of memory. The Trans Memory Collective presents a compilation of publications from the history of the trans movement in Turkey.

Narrative Power Alliance

Led by the Social Policy, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation Studies Association (SPoD), the Narrative Power Alliance brings together various advocacy groups in Turkey to resist state oppression and fight discrimination against women and LGBTI+ communities. Currently, the Alliance includes the Research Association for Democracy, Peace and Alternative Politics (DEMOS), Political Well-Being Platform, Havle Women’s Association, Positive Solidarity, Van Star Women’s Association, and KuirGaming. SPoD provides legal, psychological, and community support in the fields of gender identity and sexual orientation, while DEMOS questions the effects of state violence on disadvantaged groups and develops alternative democratic policies. Positive Solidarity offers support for individuals living with HIV. Havle Women’s Association advocates for gender equality in Muslim and broader conservative contexts; Van Star Women's Association advances gender equality and inclusivity in rural Kurdish regions. Political Well-Being Platform strives to spread an understanding of care-based organizing in Turkish politics, whereas KuirGaming creates new inclusive spaces for expression and community-building through gaming platforms. Through this collective effort, they form a long-term alliance against authoritarian oppression and build a new narrative power that challenges gender-based discrimination.

TÜRKÇE İÇİN TIKLAYIN

︎︎︎VIEW & DOWNLOAD EXHIBITION PUBLICATION HERE

︎︎︎Here is the exhibition alliance agreement signed with cultural actors in Istanbul who have agreed to host the Narrative Power Alliance: Exhibition—either in full or in part—in the event of a potential closure.

︎︎︎Press:

-Monopol Magazine, review by Ingo Arendt

-Açık Dergi, Apaçık Radyo, podcast with İlksen Mavituna

-Sanatatak, Şık Değil, Kuir Bir Sergi: Anlatı Gücü İttifakı, review by Can Memiş

-Artfulliving, Kendimizi Nasıl Yitirir, Nasıl Buluruz?, review by Ömer Uğurluoğlu

-Argonotlar.com, Anlatı Gücü İttifakı: İnadına Çatlak Açmanın Yolları, review by Alara Kuşet

-Istanbul ETC, newletter by Jennifer Hattam,

-Eva Production, video interviews, by Beste Argat Balcı

-Rast Magazine, review by Yağmur Ruken Kahraman

︎︎︎VIEW & DOWNLOAD EXHIBITION PUBLICATION HERE

︎︎︎Here is the exhibition alliance agreement signed with cultural actors in Istanbul who have agreed to host the Narrative Power Alliance: Exhibition—either in full or in part—in the event of a potential closure.

︎︎︎Press:

-Monopol Magazine, review by Ingo Arendt

-Açık Dergi, Apaçık Radyo, podcast with İlksen Mavituna

-Sanatatak, Şık Değil, Kuir Bir Sergi: Anlatı Gücü İttifakı, review by Can Memiş

-Artfulliving, Kendimizi Nasıl Yitirir, Nasıl Buluruz?, review by Ömer Uğurluoğlu

-Argonotlar.com, Anlatı Gücü İttifakı: İnadına Çatlak Açmanın Yolları, review by Alara Kuşet

-Istanbul ETC, newletter by Jennifer Hattam,

-Eva Production, video interviews, by Beste Argat Balcı

-Rast Magazine, review by Yağmur Ruken Kahraman

Zeyno Pekünlü

Connections I–II (Narrative Power Alliance Meetings), Possibilities I–II (Narrative Power Alliance Meetings), Significances I–II (Narrative Power Alliance Meetings),

6 digital prints on matte fibre paper, each 50 × 70 cm

Courtesy of the artist and SANATORIUM, Istanbul, 2025.

Zeyno Pekünlü examines the reflective residues of collective emotions, strategic discus- sions, and moments of connection through the subconscious doodles extracted from the Alliance’s meeting notes. She collects and archives these marginal patterns, which emerge alongside official meeting documentation, embodying the significance, connections, and articles of deliberation. Pressing against the formal rigidity of record-keeping, Pekünlü reframes these doodles as an alternative lexicon of collective fissures, capturing latent potential. By isolating and amplifying these margins, she proposes a mode of reading and writing on the edge of the paper, where meaning arises in the interstitial spaces between intentional discourse and subconscious articulation. These marks are not merely visual by-products but traces of com- munal thinking and collective imagination.

As theorized in Politically Red by Eduardo Cadava and Sara Nadal-Melsió, doodling functions as “fugitive labor,” resisting assimilation into the productivity of writing, delaying inscription, disrupting textual linearity, and introducing aesthetic and political indeterminacy. In Pekün- lü’s practice, this concept takes form as her elevation of doodling transforms these ephemeral marks into autonomous artifacts, resisting structured textual authority and embodying collective interruptions of conventional discourse. Pekünlü mirrors this disruption by elevating doodling from a supplementary activity to a central object of inquiry, transforming it into a sub- versive gesture against the hegemony of structured text and its attendant authority. Her collected doodles embody an expansive, mass-like quality, mapping the crowd of voices shaping collective deliberation, resonating with the text’s assertion that doodling, though often born in distraction, carries a “directionality” tied to the social and political undercurrents of its time. In Pekünlü’s hands, these marks enact a radical reconfiguration of collective authorship, multi- plying rather than resolving meaning. Neither fully writing nor fully image, these marks embody the generative instability of “thinking in other people’s heads”. By framing doodles as a collab- orative archive, Pekünlü transforms the ephemeral into a site of radical potential and marginalia into a new grammar of collective engagement, brimming with transformative potential.

Nejbir Erkol

Untitled,

text installation on flag fabric,

19 m × 24 cm,

2025.

In Arıza, Nejbir Erkol takes one of the most ubiquitous sights in Turkey—the A4 sign reading “ARIZALIDIR” (literally “out of order” or “malfunction”), typically used to mark broken public devices—and transforms it into an immersive spatial intervention. Repeated in a continuous line, the text is no longer a disposable warning of malfunction but a persistent, rhythmic gesture—a ritual of “arıza” that refuses to be ignored. The artist, while conceiving the piece, photographed these signs, realizing that the simple act of labeling a malfunction was itself an everyday performance: a refusal to fully repair what is broken, yet also a practical compromise.

A striking linguistic play lies in the tension between arıza (malfunction) and rıza (consent) in Turkish. Phonetically echoing but semantically opposed, this pairing underscores the soci- etal pressure to accept or consent (rıza) to what is broken, while arıza disrupts systems. By repeating “ARIZA” ad infinitum, Erkol emphasizes its refusal to be smoothed over; it stands in for a loop of unresolved malfunctions, an aesthetic protest against quiet acceptance. How does arıza disrupt spaces of forced rıza (e.g., public spaces or societal expectations)? Sara Ahmed’s concept of willfulness as resistance to consent could illuminate arıza as a refusal to submit to the “smooth functioning” of hetero-patriarchal systems. Arıza embodies the willful subject that disrupts normative flows, challenging the coercive structures that demand rıza (consent) to ongoing neglect.

In this physical loop, Erkol prompts us to dwell on the error and draws attention to how nonconforming subjects have long embraced the idea of “being erroneous,” finding in failure and misalignment a form of survival and community. The glitch—and by extension, the arıza—can be read as a collective congregation; there is a generative potential of error: failure, breakdown, and nonperformance as routes to new forms of agency. The in-between of arıza provides a homeland for those who cannot or will not consent—a sanctuary of possibility where refusing to function according to the system’s demands becomes an act of self-definition.

Gregg Bordowitz

AIDS CRISIS IS STILL BEGINING

Vinyl, (Exhibition copy in Turkish), 2019

Gregg Bordowitz’s banner declaring “The AIDS Crisis Is Still Beginning” confronts danger- ous narratives of closure and resolution that have emerged, particularly in the United States, around the AIDS epidemic. In contexts where access to life-saving and preventive medicine has significantly reduced transmission rates, AIDS is often relegated to the realm of history, a crisis seemingly overcome. Yet

Bordowitz’s statement challenges this temporal framing, emphasizing that HIV/AIDS is not confined to a past crisis but remains a pervasive—and une- ven—reality, one without beginning or end. It is precisely in this gap, between perceived res- olution and persistent crisis, that his banner operates as both a conceptual statement and a form of protest signage.

Bordowitz’s insistence on the immediacy of the AIDS crisis reflects his own lived experience. Diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1988, he joined ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) shortly thereafter, working collaboratively to portray people living with AIDS and to explore what he calls “the daily negotiations of living with a virus” while “grapple(ing) with the impos- sible simultaneity of hope and loss.” In his essay “Picture a Coalition,” Bordowitz elaborates: “(..) art, in the service of activism, must communicate a condition of urgency... We worked with images and texts that refused complicity with indifference. (...)”

Translated and reproduced within this exhibition, Bordowitz’s banner underscores an urgent message that resonates sharply with conditions in Turkey—where public access to preventive medication is scarce, and stigma against HIV-positive individuals remains entrenched. State rhetoric often fuels this hostility, as seen in the 2020 sermon by the President of the Directorate of Religious Affairs on the first Friday of Ramadan during the COVID-19 crisis, framing HIV as divine punishment for “illicit” behavior. The consequences of such prejudice are starkly illustrated by the case of M.E., a Syrian trans woman living with HIV who was deported after being doxed online and later killed. Together, these examples reveal a dire reality: systemic discrimination and criminalization intersect with misinformation, leaving the most vulnerable exposed to violence and neglect.

The banner functions as both an art object and an activist tool, refusing the illusion of closure and demanding that we confront the epidemic and the conditions that fuel it. The rising anti-gender movements and the state’s encroachment on LGBTQ+ rights in Turkey echo the silencing strategies employed during the first AIDS epidemic in the US. Bordowitz insist on narrative reclamation, through his grammatically “incorrect” banner. It acts as a bridge between the past and present of the ongoing crisis, HIV/AIDS, and queer activism, suggesting that the fight requires continual reinvention of how we bear witness and act in solidarity across borders, experiences, and generations.

Fatma Belkıs

Blow A Kiss, Fire A Gun

risograph-printed brochures (Narrative Power Alliance: 200 copies printed for the exhibition), 2025.

Fatma Belkıs’s Blow A Kiss, Fire A Gun, presented in the unassuming form of a brochure, subverts the medium’s conventional association with disposability and triviality, capable of puncturing the everyday through fleeting interventions, as guerrilla propaganda or unscripted happenings. Knowing that brochures are not to be read, she buried within this form an urgent narrative on public space, fear, self-defense, and legal ambiguity.

In the first chapter, Esra’s mundane day veers into a moment when she encounters a threatening presence, capturing the precariousness of everyday life for women in public spaces. The oscillation between external observations of Esra’s actions and her internal monologue creates an interplay of perspectives. Yet “disnarration”—where what remains unsaid or suppressed attains its narrative force—also shapes how her story unfolds. In those silent gaps lies an echo of every woman’s hesitation to define her fear—whether it is justified, whether she has the right to defend herself, whether the law will stand by her.

The second chapter disrupts the immersive flow through a reflexive meta-dialogue between lawyers and a writer dissecting Esra’s story. This format lays bare the text’s constructedness, spotlighting the ethical and legal implications of Esra’s actions. It mimics judicial processes, where women’s testimonies are tested against standards that neglect subjective trauma. Such a shift from narrative to meta-narrative shows the story taken apart and reconsidered, reminding us that Esra’s account is no monolith but a patchwork of memory, legal definitions, and emotional truth. A dimension of the work arises from the tension between narrative power and powerlessness. The lawyers’ back-and-forth underscores systemic inadequacies around self-defense and autonomy, as the law relies on evidence that cannot convey the emotional toll of violent encounters. By leaving key facts ambiguous—did Esra kill the man or did he die otherwise?—the text highlights how consequential aspects can remain unprovable. This ambiguity drives readers to reckon with the limits of law and narrative. In a broader sense, it invites reflection on how certain voices—particularly women’s—may be sidelined or discredited, revealing a narrative about personal survival and collective struggles to be heard and believed.

Üzüm Derin Solak

Save the Night from Darkness

fine art photograph printed on composite material, 73 × 110 cm, 2025.

Üzüm Derin Solak’s photograph casts two figures—a trans woman and a male-presenting nonbinary individual—against Istanbul’s shimmering waters bridging two continents, also the spectrum of bodies so often erased. This photograph emerges in the wake of Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, a framework once poised to protect women and LGBTQI+ communities from gender-based violence. By stepping away from its commitments, the state revealed a deeper rift, especially for trans and genderqueer bodies whose lives remained largely unspoken in mainstream discussions of gender violence.

This strategical silence—arising from a broader societal tendency to advocate more strongly against femicide than violence targeting trans and queer bodies, with fears that explicitly pronouncing the rights of queer individuals might jeopardize the tenuous recognition and already failed protections afforded to women—spurred Solak—a trans woman herself—to ask how one might continue to photograph Istanbul in the absence of the very protections once associated with the city’s name.

Here, between two shores, they rewrite the city’s name, untethered from the old script that failed to uphold them. In liquid reflection, they find a mirror for their ever-shifting bodies, the fluid, living testament of who they have always been. The Bosphorus becomes a site of reclamation, its phosphorescent surface evoking a realm of possibility that transcends the restrictions imposed on land. While formal statutes may deny protections, the water’s expansiveness suggests an alternative space where identities and rights can be renewed. And so the photograph stands as an elegy—not only for Istanbul but for every promise broken. An elegy, yes, but also an invocation of future possibilities: if existing structures fail, there remains, in the uncontainable flow of water and the unbreakable spirit of these figures, an ever-present chance to redefine community and belonging.

Furkan Öztekin (with Ceyhan Fırat)

Fragmented Landscapes

paper collage on MDF, 17 × 24.5 cm, 8 pieces, 2025

The Past Withdraws

paper collage on MDF and found object, 20 × 29 cm (framed 23 × 31.5 cm), 8 pieces, 2025

Interventions, Notes, Traces

installation (digital photographs, wire mesh, painting, found object), variable dimensions, 2025.

Furkan Öztekin’s ongoing engagement with the late trans-poet-activist Ceyhan Fırat’s archive demonstrates how narrative-making is always evolving, resisting a single coherent storyline. Since 2019, beginning when Ceyhan was still alive, Öztekin has collaborated with her by collecting, reconfiguring, and responding to texts, photos, and found objects from Fırat's corpus and archive, while also incorporating elements from his own archive, which includes photographs of Ülker Sokak and deeply personal items such as his journals. Fırat’s declaration, “This is not my archive; it is our archive,” became a guiding ethos for their collaboration, emphasizing shared ownership. Each work—from fictional texts they co-wrote to Öztekin’s reproduction of a crown Ceyhan used to wear, his attempts to capture sites from her life in Ülker Sokak today, and the color hue (“pejmürde pembe”) she described in her poems—becomes an intertemporal, interpersonal assemblage, embodying “horizontal and vertical intersections of memory.” Since Ceyhan’s passing, the archive has taken on an even more elusive quality: it continues to speak, yet its storyteller is no longer present to clarify contradictions or fill in the gaps. By embedding these evolving relationships within his work, Öztekin expands upon Fırat’s legacy, crafting poetic assemblages that are as much about absence and disjunction as they are about connection and continuity. In a recent interview for writer/researcher Çağla Özbek’s book Unreliable Narrator, Öztekin discusses the slippery nature of Ceyhan’s story—a biography shaped by multiple voices and contested truths. This dialogue prompted him to revisit his methods and more explicitly explore the concept of the “unreliable narrator” in his new 34 35 body of work. What emerges is not a fixed chronology but a fluid assemblage of recollections, omissions, and fictional elements.

Öztekin performs a meta-critique of his practice—collaboration, inspiration, and appropriation— by presenting photographs mounted on MDF, wire mesh, ink drawings on paper, and found objects. These materials are arranged in frames, yet they also slip beyond them, hinting at a narrative that refuses containment. Meanwhile, wire mesh snakes through the installation— sometimes contained within frames, sometimes sprawling across the assemblage—tying disparate scenes together, even as it underscores the archive’s inherent contradictions. Within this assemblage, a burned portrait of Fırat, its edges charred and curling, becomes a visceral reminder of erasure and survival. A luminous sheet of yellow fabric, suspended against a dark, expansive landscape, hovers as a spectral presence, resisting dissolution. Strands of woven wire, looping, twisting, and threading through the compositions, anchor these works in a shared material and symbolic language. This wire—repurposed from Öztekin’s recreation of Fırat’s crown—enacts a poetics of continuity and reconfiguration, weaving together fragmented narratives and temporalities.

Kiki ggNash

Gullüm Perisi

oil on two canvases, 150 × 170 cm and 20 × 20 cm, 2025.

Kiki ggNash’s painting, conceived as a “family portrait” of her selves, conjures child, adolescent, adult, pre-transition, and post-transition identities on a single visual plane, taking the place of familial photographs she never had or that were withheld. Multiple temporalities tangle here, reflecting that the trans body is in a constant state of negotiation between what was and what is becoming. Revisiting fractured and inaccessible pasts—especially from before she ran away from her birth ‘family’ and never returned—Kiki asks, “How can someone with no photographs or artifacts truly exist in memory?” And if memory serves her right? She adds another layer to the composition by burning the portrayed versions of herself that she cannot or does not wish to associate with anymore, creating what functions as a “counter-archive” in the absence of institutional or familial records. Kiki’s personal story underscores the precarious relationship trans subjectivity often has with inherited genealogies, favoring new frameworks for belonging. By painting these fractured “family” portraits, she situates herself among her ghosts, standing in for an absent or unsupportive archive that refused to keep her record, culminating in a layered canvas that is at once refuge and battlefield. This act of burning becomes a ritual of both destruction and reconstruction—an attempt to grapple with memory’s erasures while making space for a new collective self-image. Burning the canvas is an ongoing technique Kiki employs; in a previous work Show the Uncles Your Gender (2023), she inscribed transphobic slurs onto the surface, then burned those texts away, leaving painterly gestures as living scars. Through paint and flame, she continues to forge her identity on her own terms, refusing to let erasure define her story.

Cansu Yıldıran and Havle Women’s Association (Havle Kadın Derneği)

The Fluidity of (Non)Covering

photographic installation, 350 photographs (each 21 × 14 cm), 2025.

Cansu Yıldıran’s practice, undertaken with the Havle Women’s Association, engenders a re-visioning of Muslim women’s visibility by fragmenting and reassembling corporeal and sartorial signifiers. Drawing on Havle’s slogan “the headscarf is fluid,” Yıldıran and members of Havle, through strategically suspending photographs of hijab prints, skin, and bodily details— eyes, hands, hair—destabilize fixed gazes by situating veiling practices within broader contexts of agency and relationality. They resist reductive binaries of veiled/unveiled, pushing beyond Orientalist tropes that construe Muslim women as either oppressed, without agency, or exotic, hidden, and in need of discovery.

By fracturing images, the installation foregrounds crucial questions: how do the bodies of Muslim women enter public debate? Gender, religion, race, class, and sexual orientation intersect to shape how Muslim women experience and negotiate visibility, often confronting multiple forms of discrimination—Islamophobia, sexism, racism, and homophobia. Suspended, fluid, fragmented photos underscore that visibility is neither strictly present nor absent but an ongoing negotiation of what is disclosed and what remains concealed. This perspective parallels ethical frameworks that uphold women’s rights to self-determination in public and private spaces. Wearing the headscarf can make Muslim women hyper-visible in societies where the hijab is construed as “other” or symbolic of political tension. At the same time, it can function as a deliberate mode of modesty and boundary-drawing, asserting a woman’s choice to control how her body is seen (or consumed) by external gazes.

The fragmented aesthetic thus reveals the multi-layered identities of the Havle community— spanning diverse backgrounds, experiences, and modes of piety—while challenging spectators to unlearn habitual ways of looking. By juxtaposing glimpses of hair alongside textiles traditionally associated with concealment, the installation both queers and pluralizes the iconography of Muslim femininity. In so doing, Yıldıran and Havle collectively reject cultural scripts that either hypersexualize or invisibilize them, offering a counter-testimony with embodied narratives.

belit sağ

ruken ve bahisdışı kızkardeşler (in production)

single-channel video, 10 minutes, 2025;

Sevil

single-channel video, 8′19″, 2024.

Belit Sağ’s two video works juxtapose the accounts of artist Sevil Tunaboylu and activist/ researcher Ruken Ay from Van Star Women Organisation, offering a layered portrait of censorship and self-censorship. Tunaboylu recounts how her painting was slashed at an exhibition. Though devastating in itself, the act of vandalism was compounded by her subsequent anxieties about re-exhibiting the damaged work or reproducing its image in a publication. Even after the physical assault ended, Tunaboylu grappled with the lingering pressure to conceal her creation, repeatedly questioning whether showing it might invite further harm. Her story exposes how external violence morphs into internalized fear, fueling a cycle of guilt, shame, and reluctant acquiescence.

In parallel, Rüken Ay shares the obstacles she faced while attempting to build a digital memory museum. She found local and state archives sealed off or uncooperative, heard repeated warnings that her subject was “dangerous,” and even confronted subtle patriarchal refusals from within her community. Shrouded in a climate of suspicion, her project teetered between the urgency of bearing witness and the trepidation of transgressing unspoken, undocumented, unrecognized state violence. Like Tunaboylu, she wrestles with a form of enforced silence, wondering if her commitment to representing Kurdish women’s histories might imperil herself or others.

Desktop recordings capture Sevil Tunaboylu and Rüken Ay telling their stories with all the hesitations, stutters, and confessional tones that come from talking to a camera (and an artist) at a distance. The screens become a visual metaphor for the tenuous boundary between what is “public” and “private,” revealing just how quickly a protected dialogue might morph into a risky exchange. Their bodily presence on screen becomes a double gesture—asserting their right to speak, yet never entirely liberated from the watchful eyes of those who would silence them. Sağ is orchestrating the conditions under which these two women’s narratives can be shared and re-archived, assuming a position akin to a “vulnerable observer”—someone who documents the fragile, precarious nature of the testimony, but also shapes its presentation. Sağ becomes the connector between two parallel stories of Kurdish women’s erasure, using the logic of screen capture to map a broader political terrain. Despite all obstacles, these stories must exist somewhere—on a hard drive, in a conversation, in a desktop film. Acts of memory-making, bearing witness, and feminist solidarity break through the frame of what official histories would rather keep outside the screen.

Serdar Soydan

Archival research materials on Adnan Pekak, Kudret Şandra, Zenne Necdet

2025

Serdar Soydan’s archival exploration positions Adnan Pekak, a gifted singer overshadowed by Zeki Müren who passed away in anonymity; Zenne Necdet, a pioneering stage artist renowned for portraying female roles on stage; and Kudret Şandra, a daring dancer who eventually embraced spirituality, as vibrant yet overshadowed gender-bender performers of Turkish popular culture from the recent past. Soydan foregrounds the resourcefulness of these performers, who navigated strict censorship, moral codes, and shifting public tastes. By weaving together fragments of personal testimony, film stills, press clippings, and promotional posters, Soydan’s work questions what gets remembered. Soydan’s approach unearths the complex interplay between personal authenticity and a sensationalist media culture that often framed them with ridicule or censure. Rather than merely collecting stray press clippings, lurid headlines, and promotional materials, Soydan confronts the adversarial tones and sweeping generalizations of these sources by placing his own carefully researched biographies side by side with the very narratives that sought to trivialize or marginalize these figures. In doing so, he not only recovers their legacies but also reveals how the narratives of media tropes, censorship, and social stigmas have persistently shaped—or distorted—public perceptions of queer lives. Each panel that Soydan constructs can be seen as both a meticulous collage of ephemera and a political act of reclamation, inviting viewers to encounter the layered interplay between individual mythmaking, social aspiration, and systemic silencing. Soydan functions as a media archaeologist who excavates the fleeting realities of entertainment culture in mid-twentieth- century Turkey, reminding us that memory itself is often the first battleground for collective liberation.

Read biographical texts on Adnan Pekak, Kudret Şandra, Zenne Necdet written by Serdar Soydan here

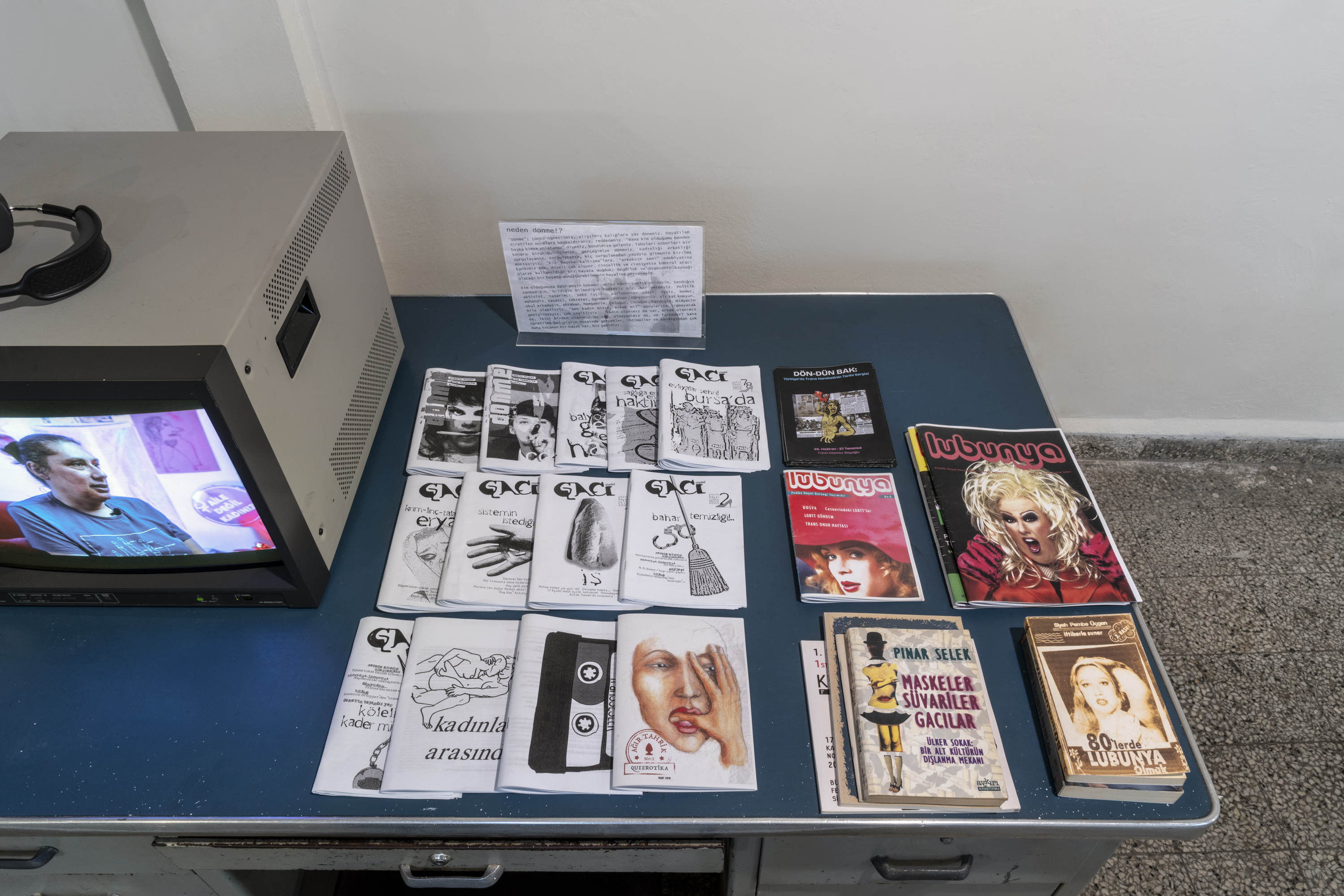

Trans Memory Collective

Action videos from the Turkish trans movement

(1987 March Against Battering; 2010 and 2014 Trans Pride Marches; 2003–2022 May 1 trans contingents in Antakya, Antalya, Ankara, Istanbul, Kocaeli, Mersin; 2016 Çağla Joker; 2016 and 2017 Hande Kader “Trans Murders Are Political” Marches, Istanbul), 2025.

Publications from the Turkish trans movement: issues of Gacı, Dönme, Lubunya magazines;

Do You Remember? Oral History Study Video, 30′40″, 2024.

The exhibition also includes a selection from “Dön-Dün Bak: The History of the Trans Movement in Turkey,” curated by the Trans Pride Committee. Originally developed for Trans Pride Week—first held in 2010 and marking its tenth edition this year under the theme “the perpetrator is the state.”—it was a pioneering showcase of trans experiences and activism, featuring archival materials, personal testimonies, and historic artifacts. In July 2024, however, the Turkish government forcibly shut down this influential exhibition. In response, members of the Trans Pride Committee formed the Trans Memory Collective, determined to preserve and re-present key elements from the closed show. They have gathered pivotal trans publications— Gacı, Lubunya, and Dönme—which offer insight into the shifting debates that have shaped the trans movement over the years. Central to this reimagined display are videos in continuous loop, drawn from various Trans Pride gatherings and public demonstrations— from the 1987 women’s marches against violence, to trans contingents in 1st May marches, to Trans Pride footage from the past decade. These short clips and raw recordings depict chanting, speeches, and public performances, capturing a broad array of participants—activists, allies, and curious passersby. Moments of direct confrontation with authorities are juxtaposed with collective joy and mutual care, illustrating the resilience and determination that continue to define those demonstrations.

.

.