TRANS MUSE AND MOTHER: “I” WITHIN “WE” AND “WE” WITHIN “I”

Kübra Uzun & Çiçek Çocuk, videostill from Our Diamond Glasses, 2021, Commissioned by Pera Museum, İstanbul

Kübra Uzun & Çiçek Çocuk, videostill from Our Diamond Glasses, 2021, Commissioned by Pera Museum, İstanbul

TEXT, MARCH 2024

Curator Alper Turan writes on artist/performer Kübra Uzun, a.k.a. Q-BRA, trans muse for both local and international artists, who redefines the traditional concept of a gendered muse. Alper Turan writes about how Kübra Uzun asserts her agency and shares knowledge of the past four decades of LGBTQIA+ history in Turkey including the artistic lineage of Bülent Ersoy, Zeki Müren, and Huysuz Virjin (Cranky Virjin).

originally published on Protodispatch,

available in Turkish on argonotlar.com

in Thai on grounddcontrol.th

Kübra Uzun emerges as a contemporary set of personas, in the artistic lineage of Bülent Ersoy, Zeki Müren, and Huysuz Virjin (Cranky Virjin). She is both the successor of these three predecessors' heritages and their counterpoints. Kübra Uzun’s work and personas are ungovernable and interlocked, her queer styles are always performative; whether on stage or off. Or, perhaps more accurately the stage is an endless space and the performance never ends. Kübra Uzun, a.k.a. Q-BRA, is an İstanbul-based singer, songwriter, performance artist, and DJ; an LGBTQIA+ rights activist, micro-celebrity, revolutionary trans mother, and community organizer.

Born in turbulent 1980, right after the coup that turned the life of Bülent Ersoy into endless grief, and raised during the first decades of Turkey’s neoliberalism, which allowed for the flourishing of personalized freedom that gave rise to the stardom of Ersoy and Huysuz. Kübra Uzun navigated her formative years amidst a backdrop of cultural and societal transformation. She showed an early affinity for music at the age of nine. Her aspirations towards a music career were abruptly halted by her witnessing her father’s aggression towards her mother, a trauma that prevented her from completing her audition process at Moscow P. I. Tchaikovsky Conservatory’s piano department. She found solace and expression in high school music groups, pursued musical acting studies, and immersed herself in theatrical productions and musicals. She also contributed her vocal talents as a backing singer for pop icons Candan Erçetin and Nilüfer.

During that time she started cross-dressing in the privacy of her home. Returning from work or school, she would don a wig and makeup, immersing herself in online chat sites under various aliases. This engagement wasn't just about the anonymity or the thrill of a temporary transformation; it was the performative aspect—the immediate reaction to this performance and its potential to evolve into something more—that captivated her. Unlike narratives of being "trapped in the wrong body," her journey wasn't rooted in a dichotomy of male/female or a deep-seated feeling of being a woman. Instead, she was drawn to the process for the enjoyment of it and the pleasure of the performance. She underwent hormone therapy, rhinoplasty, breast augmentation, and laser treatment, and in 2015, Kübra Uzun was born.

For three years after her transition, Uzun engaged in sex work. She went through a process in which she questioned, saw, and experienced how to move in life through a new body. She performed a hypersexual femme persona with long black hair, flashy attire, and a femme-fatale attitude. In their analysis of “fem,” Rosza Daniel Lang/Levitsky asserts: ‘‘Being a fem ... meant being visible .... It meant making yourself recognizable so that if you need help, your people will know you, so that if they need help, they know you’ll have their backs. Fem style marks its bearer as noticeably identified with other queers.’’ [1] This fem style is Uzun’s visibility manifestation - performing an otherworldly diva akin to Ersoy, Müren, or Huysuz with one difference: her stage is her life, and she is building a support structure through it.

Kübra Uzun, photo by Deniz Erol, 2016

Kübra Uzun, photo by Deniz Erol, 2016From a very early stage in her bodily exploration, Uzun started disseminating her personas, and she took every opportunity she could to perform. For the video piece Vintage Porn,[2] she sings arias and demonstrates and re-enacts her regular sex work performance to a camera lens, displaying her blossoming tits and how she handstands for customers or talks with them.

Q-BRA as Muse

Over the years, Uzun has established herself as a trans muse for both local and international artists, redefining the traditional concept of a gendered muse. Historically, the muse is the lover, spouse, and intimate friend of the creator. The muse has been perceived as a passive source of inspiration due to their disposition, charisma, wisdom, sophistication, and eroticism. In her capacity as a trans muse, Uzun transcends mere objectification, firmly rejecting any reduction to a specimen or a subject of a study. She is not to be pigeonholed as a mere curiosity and static image of otherness; she cannot be harassed by a male gaze. In her performance for the camera, even when directed by another, Uzun asserts her agency, solidifying her self-determination with unequivocal clarity. She creates a living style, a performance, a persona that defies capture and nullifies any hierarchical position that would claim ownership of her body, image, or narrative. On occasion, she may offer her image to collaborators, thereby enabling a representation that accrues (cultural) capital over her personas. Regardless, one never imagines this being exploitation. Instead, her participation is expansive and conducive to multiplying, shattering her many or various selves into friends.

Uzun’s muse work is innately collaborative. Muses are historically considered distinct from the people who organize, teach, befriend, mentor, or support artists. Uzun, rather, reclaims care work; collaborating with and inspiring others by way of creating spaces for others is her muse work. Over time, as Uzun carved out her niche, she re-engaged with social life and ventured into DJing, thus birthing a new persona: Q-BRA. DJing allowed her to blend her past experiences with her aspirations, manifesting a unique presence in the music and nightlife scene, where she can be on the stage,orchestrating a communal space. The sets she curates are ‘’sonic journeys’’ and ‘’mood sculptures,’’ revamping minoritarian life through the sonic archive of the community with a richness of samples from queer ancestors.[3] Dissatisfied with merely playing songs, she returned to her roots in live performance, adopting a cabaret-style approach by weaving together a collage of songs from musicals and arias. Beyond her performances, she acts as a transformative trans mother figure to younger generations of trans and queer individuals, guiding them into the world of performance through the burgeoning invention of local voguing and ballroom scenes that the popularity of drag race shows created in the West.

In a video interview, Uzun notably begins her statements with "I," only to pivot to "we" emphasizing the indivisible link between the individual and the collective, underscoring the intertwined identity of “I” within “we” and “we” within “I.”

Every moment that I am on stage, that we are on stage, that I sing, that we sing, that I perform, that we perform, are moments that nourish us, that we shout out, that we express ourselves in the name of our existence. Activism is each of those moments, so for each of us, we become the real subject of activism through performance.'

Uzun’s Predecessors

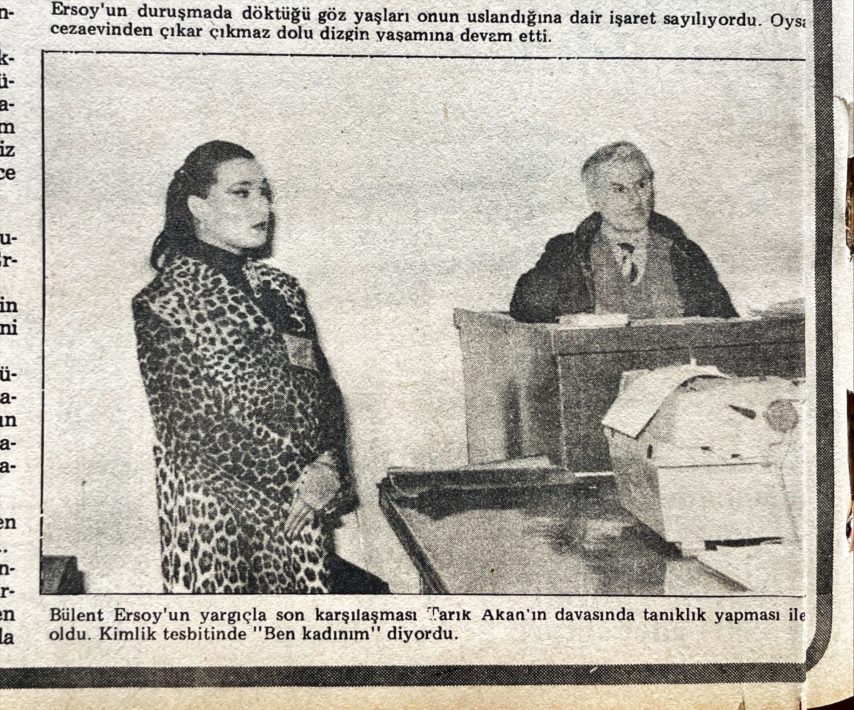

On a tense autumn evening in 1980, just before a military coup would change Turkey's democracy forever, Bülent Ersoy, a transgender singer, defied expectations by taking the stage. Ersoy, undergoing her transition under public scrutiny, faced an audience curious about her hormone therapy. Their chants for her to reveal her new breasts led to a moment of bold exhibitionism, more a powerful declaration of self-determination than mere sensationalism, at a time when personal freedoms were under threat. Prosecutors attacked this act, claiming that it undermined Turkey's moral values and thus ironically affirming Ersoy's femininity, which the law denied. Her lawyer countered, arguing that since the state saw Ersoy as male, her chest exposure wasn't indecent by their standards. The 1980s regime sought to erase "public immorality," banning MTF trans and cross-dressing performers from the stage and targeting Ersoy and others who “resemble more a woman than a man in their clothes and behavior onstage.”[4] This ban extended beyond the stage, leading to widespread persecution of trans individuals that included torture, forced changes to their appearance, and deportation from cities.

Son Havadis, 1980, Newspaper clipping

Bulvar, 1982, Newspaper clipping

Labeled a "disgrace to society," Ersoy responded with her song “Yüz Karası (Disgraced),” which includes lyrics that oscillate between "we" and "I" to highlight the collective plight of sexual minorities:[5]

Alone or the center of gossip,

We endure pain everywhere, like mourning doves.

You'd cry too, in such despair,

When my fate was sealed, angels cried above (...)[7]

After her gender reassignment surgery, Ersoy confronted severe legal battles for gender recognition and to lift the ban on her performances. The courts denied the legitimacy of her transition, dismissively categorizing her as a "male homosexual" and thus failing to recognize her womanhood, citing rigid medical and legal interpretations that restricted bodily autonomy. It took eight years for Ersoy to reclaim her stage presence in Turkey and be legally recognized as a woman with a "pink ID," a milestone that mirrored the emerging neoliberal government's distinct brand of "freedom."

Despite her journey with gender and sexual identity, however, Ersoy did not embrace advocacy for LGBTIQ+ rights. Instead, she aligned with conservative and nationalist ideals, distancing herself from the LGBTIQ+ community and even denounced homosexuality on the symbolic day of the 2016 Pride parade in İstanbul, while queers were being brutally dispersed. A month later, trans activist Hande Kader was found raped, mutilated, and burned. Under the aggressively authoritarian Erdogan regime, Turkey became the epicenter of trans murder in Europe.

Alongside Ersoy, notable figures like Huysuz Virjin (Cranky Virjin) and Zeki Müren also challenged gender norms and faced public performance and broadcasting bans. Dubbed the "Turkish Liberace," Müren was celebrated not only for his musical talent but also as a secular symbol within the militarist regime, epitomizing the opposite of the provincial, pre-modern, non-Western. Müren's increasingly flamboyant costumes, from miniskirts to platform shoes, were his unique style rather than a statement of his sexuality. Despite his extravagant appearance, he denied any implications about his sexuality, claiming a style more akin to that of Caesar, Brutus, or the prince from outer space, rather than an average Turkish man.8 Behind the scenes, Müren supported gay clubs and had relationships with high-profile men. Yet, his public persona, crafted through media portrayals and his roles in films, was carefully curated to appear heterosexual. His music, expressing themes of unattainable love and melancholy, resonated deeply with his audience and became a medium through which he communicated his innermost feelings. His tremendous discography is filled with songs crying out about impossible love, fear of abandonment, and melancholy, which is ‘‘the immanent vehicle of communication between Müren and his audience.”[9]

Without telling anyone

Without our longing is known

Without being seen in hidden

We’ll meet in dreams

We'll meet with this song

In line with the regime’s militarist projection, Müren’s fans call him “Pasha,” a heroic military commander. He proudly embraced this moniker, semantically diverting public attention away from his glitters and toward masculine embodiment. According to urban legend goes, once after being asked about this nickname, Müren answered, ‘‘They will not call me a faggot if they call me Pasha.’’[10] This protective shield, however, petrified his military engagement. Upon his death from a heart attack while performing on stage, Müren bequeathed his estate to a foundation that aids Turkish soldiers and veterans. It’s hard to say whether this decision was a cunning act to tease and corner the Turkish military, which is famously known as the world's largest gay porn archive.[11] Today, unfortunately, both the copyrights to his songs and his public image are controlled by the Turkish military; Müren’s biography cannot be published, and anyone wishing to cover his songs must pay royalties to the military.

Müren, Ersoy, and Huysuz have largely been seen as queer predecessors while simultaneously being criticized for not being outspoken and brave enough to ‘‘out’’ themselves. I question the idea of defining gender non-conformist personas as queer people, finding this both anachronistic and Western-centric, as well as an unnecessary constraint of an identity category. I don’t expect transparency from public figures, and performance of coming out, as they are also in precarious positions. I desire to see them having queer personas/styles or doing queer acts instead of being queer; I prefer looking at their lives and works to locate queer corners and strategies that are already ingrained in the collective memory of Turkish society.

The pandemic left many LGBTIQ+ nightlife performers in Turkey without work, exacerbating their precarious situation. Uzun responded by co-founding Through the Window, an online platform that leverages social media and videoconferencing to present digital art, performances, and events by queer artists from Turkey and the Netherlands. By providing both visibility and financial support, this initiative not only spotlighted underrepresented local artists but also inspired those outside the traditional art scene to create and share their work. For Uzun, the project was about more than just showcasing art; it was about creating communal spaces for expression and connection, filling the void left by the closure of physical venues.

Since 2015, Turkey has seen a clampdown on Pride events, with authorities banning even minor gatherings during Pride season. Nevertheless, each year, hundreds have courageously challenged these bans, striving to hold the Istanbul Pride March. Their innovative efforts to circumvent restrictions have often been met with harsh police tactics, including blockades, tear gas, and transit shutdowns, resulting in 25 arrests in 2021 and a sharp rise to 373 in 2022. [12]

Kübra Uzun & Mr. Sür, 'ALAN 2020', song video, 2021

Today’s Unfolding Realities

As 2020's Pride season neared, Uzun channeled the spirit of resilience into music, creating “ALAN2020 (SPACE2020).”[13] The song emerged as the anthem of that year's Pride. Members from the community enthusiastically shared videos of themselves dancing to the song, which were then woven together into a final video clip. The song’s lyrics

We've had enough, we riot till the end

Off of our sight if you think we pick sides

Rock rock shock shock

Look behind, look with pride

Winning it wasn't the easiest ride

I'm free my love!

Down with the hate, let the flowers parade

Bloomin to blossom, overflow from the high tops

Seven hills, seven colors, we're lubunya[14]

Colors don't fade and nor do our voices

Collaborating with artist/director Onur Karaoğlu, Uzun brought to life A Trans History Sung [15] an interdisciplinary performance that weaves together elements of theater, musicals, and the digital arts. This performance made its debut through Instagram's live-streaming feature, on an account created for A Trans History Sung. Afterward, the digital performance, together with audience comments, shared pictures, and further meta-narratives, was edited into a four-channel video that was showcased as part of the Volksbühne Berlin's Next Waves Theater program.

The performance shows a pivotal moment in Uzun’s life, marked by a significant decision preceding her relocation to Berlin. Throughout the performance, Uzun narrates the defining stories of her life as a trans person in Istanbul, interspersing them with performances of songs that hold personal and collective significance. The artist reflects, "We listen to my memories, the shared recollections, creating a digital monument; even if I leave İstanbul, this Instagram account will stand as a testament. Is leaving harder, or is it staying? Who is forced to leave? In this performance, I depart, but is departure what I truly desire?"

In 2021, Uzun, inspired by the cheeky canons that Mozart wrote for his friends, such as “Leck mich im Arsch (Kiss My Ass),” offered a fresh take. Adapting Mozart’s four-part canon with Lubunca16 lyrics and recording it a cappella, Uzun created Koli Canon (Fuckbuddy Canon). A Canon— a musical form and technique based on the principle of imitation, in which an initial melody is imitated at a specified time interval by more parts—is interesting for its political premise. Each voice, while harmonizing the same melody, infuses it with uniquely different tones, thereby embedding their positions within a shared musical framework and achieving a blend of personal expression and collective anonymity.

Kübra Uzun, Still from 'Koli Kanonu' (Fuckbuddy Cannon), 2021

Kübra Uzun, Still from 'Koli Kanonu' (Fuckbuddy Cannon), 2021The “Koli Canon,” is sung by four fictional personas Uzun is impersonating: Butch Berna, Dikiz (Voyeur) Jülyet, Madame Sipsi, and Kübra Uzun herself. Set against the backdrop of a casual tea gathering at Uzun's home, the canon unfolds, illustrating the intertwined, humorous, and empowered narratives of these characters. These new personas, whom Uzun calls ‘‘new friends’’ and for whom she fabricates critical fabulations are reminiscent of the universes of Huysuz Virjin, Zeki Müren, or Bülent Ersoy: canonical camp personas with whom Uzun disassociates herself politically despite appropriating and sampling their styles. Together with fictional life narratives, styles, costumes, lyrics, and sound, Koli Kanonu positions itself as a music video complete with artwork that employs a mode of queer counterpublic world-making. In another video, "Jülyet's Habanera," Uzun reimagines Bizet's iconic piece from Carmen, again with lyrics in Lubunca, embodying her personas. Uzun, in her Dikiz Jülyet persona, sings:

‘The ass is mine, the tits are mine

Who I do is just for me to decide

I’ll choose whose job is to be done:

A boy-toy’s or a DILF’s or anyone’s’

Kübra Uzun’s lives, works, and personas create an ‘‘endless theater of everyday life that determines the real.’’ Nullifying the distance between ontology and performance, she never impersonates a persona she does not invent, because there are no past or afterlives of them. Her performance continues her ‘‘world-making project,’’ that is, it ‘‘endeavor[s] to create worlds, where the concept of ‘world,’ distinct from ‘public’’ ... differs from community or group because it necessarily includes more people than can be identified, more spaces than can be mapped beyond a few reference points, modes of feeling that can be learned rather than borrowed from society.”[17]

Kübra Uzun, Still from 'Julyet's Habanera', 2022.

NOTES:

- Rosza Daniel Lang/Levitsky, ‘‘Our Own Words: Fem & Trans, Past & Future,’’ e-flux 117( April 2021): 20.

- Vintage Porn - Part I,2014. Directed by Emre Busse & Burak Erkil, Produced by Pornceptual, Act: Q-BRA, Performance: Selin Tural, Make-up: Deniz Eda Göze, Soundtracks: “Votre Toast” by Bizet, “Vogue” by Madonna https://vimeo.com/110359301.

- Paul Miller, “Algorithms: Erasures and the Art of Memory,” in Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music, ed. Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner, rev. ed. (Bloomsbury Academic, 2017), 472.

- “Bülent Ersoy giyimini düzeltmesi için emniyete çağrılarak uyarıldı,” Milliyet, January 28, 1981.

- Başak Ertür and Alisa Lebow, "Coup de Genre: The Trials and Tribulations of Bülent Ersoy," Theory & Event 17.1 (2014).

- Translation by Bülent Somay, through Başak and Lebow, "Coup de Genre: The Trials and Tribulations of Bülent Ersoy."

- Martin Stokes, "The Tearful Public Sphere: Turkey’s ‘Sun of Art,’ Zeki Müren," in Music and Gender: Perspectives from the Mediterranean, ed. Tullia Magrini (Chicago: the University of Chicago Press, 2003), 307-328.

- Eser Selen, "The Stage: A Space for Queer Subjectification in Contemporary Turkey," Gender, Place & Culture 19.6 (2012): 738.

- Selen, “The Stage,”737.

- Until recently, gay men in Turkey seeking exemption from compulsory military service, which prohibits the participation of “sick” gay men, were compelled to submit photographic or video evidence of themselves engaging in sexual intercourse, specifically in a passive role, to validate their sexual orientation.

- https://www.npr.org/2022/06/27...

- Music: Mx. Sür and Kübra Uzun; Lyrics: Kübra Uzun; Director: Efe Mine; Producer: XSM Recordings; Mixing: Salih Topuz; Mastering: Çağan Tunalı; Mx. Sür and Kübra Uzun's Costume Design: AntreSx; Mx. Sür & Kübra Uzun's Makeup: tusidi; Translation: Willie Ray & Madır Öktiş.

- “Queer” in Lubunca.

- Video version: https://vimeo.com/485413101/ddddcc338f; Instagram page: @atranshistorysung

Conceived and Performed by Kübra Uzun, Conceived and Directed by Onur Karaoğlu, Video Editing and Sound by Emre Kaya, Additional Camera by Metin Akdemir FOX, Arya Sezer, Translation by Nazım Dikbaş, Additional Translation by Onur Karaoğlu - Lubunca is a secret Turkish cant and slang used by sex workers and the LGBTIQ+ community in Turkey; derived from slang used by Romani people, it also uses terms from other languages, including Greek, Arabic, Armenian, and French.

- Berlant, Lauren, and Michael Warner. "Sex in public." Critical inquiry 24.2 (1998): 558

Q is non-existent in Turkish

Text

January 2021

Published within the publication of ,

Re: [aap_2019] ARTER MUSEUM, ISTANBUL

The publication titled Re: [aap_2019], produced in conjunction with the inaugural edition of the Arter Research Programme that took place between October 2019 and July 2020, follows the trajectory of the individual research of participants and the collective experience shared throughout the programme.During the 10-month-long programme, participants took a collective turn towards working on the publication. They decided to create ten different drive folders, one for each month, to which each participant uploaded multimedia content. At the end of this process, each participant became the editor of a specific month, engaging with borrowed content in a loose and creative manner.

I allowed myself to delve into each folder, appropriating images, texts, and even final projects from other participants for the publication. My autofictional text was led by these materials, often using them as footnotes whose functions shift throughout the text. Although the text is self-contained, it was guided by the works of others, aligning with the conceptual framework of this fictional story.

The story follows a first-person narration of my time as an intern at the Schwules Museum. I explored the museum's archives, stayed in the now-vacant apartment of a recently deceased board member, and examined his personal objects both at home and within the museum's collection. The presence of the first ghostly host unearth to the appearance of another. This text is an experiment where footnotes take over the body, a narrative on leaky queer archives, a collection of orgy with guests, ghosts, and hosts.

Arter Research Programme 2019-2020 Participants: Alper Turan, Ayşe İdil İdil, Deniz Aktaş, Eser Epözdemir, Ezgi Tok, Gizem Karakaş, Neslihan Koyuncu Bali, Nora Tataryan, Sarp Renk Özer.

300 pages, 16.5 x 24 cm

Turkish | English

ISBN 978-605-69490-7-4

Edited by: İz Öztat and Merve Ünsal

Translated into English by: Ekin Can Göksoy, Çağla Özbek, Aslı Seven, and Merve Ünsal

Design: Okay Karadayılar and Ali Taptık (Onagöre)