How does the body take shape under pressure?

Exhibition

Natalia Gurova, Nihat Karataşlı, Zeynep Kayan, Can Küçük, İz Öztat and Ann Antidote, Dorian Sarı, Toni Schmale, Carlos Vergara, Cansu Yıldıran

Curated by Alper Turan and Nazım Ünal Yılmaz

18 May 2022–15 June 2022

Queer Museum Vienna & Volkskundenmuseum, Vienna

How does the body take shape under pressure? brings together an international group of contemporary artists whose works come from the myriad experiences of pressure and questioning the dynamics of unproportional forces. Working between the lines of passive and defensive, social and intimate, pressure and pleasure; the exhibition presents artists’ allegorical positions to ponder political repression against queer and feminist existences.

Queer Museum Vienna is supported by Josefstadt and WASt - Wiener Antidiskriminierungsstelle. Dorian Sari's participation in the exhibition is supported by

The Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia. Exhibition documentation: Flavio Palasciano.

![İz Öztat, Haz/Cızzz I [Pleasure/Sizzle II], 2019. Sponge, needle, artificial leather, tassel, tape, cardboard toilet paper tubes, wall mount. 55 x 8 x 5 cm.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/9b1de6d7ee81af0fc0fcee376dbdc98a1b228bea9d412a9d406d854738822740/9_HowDoesTheBodyTakeShapeUnderPressure_QueerMuseum_Vienna_2022.jpg)

![İz Öztat, Haz/Cızzz II [Pleasure/Sizzle I]. 2019. Needles, thread, whisk, feathery plant, parchment, tape, cardboard toilet paper tubes, wall mount. 60 x 30 x 5 cm](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/e80d1d51625ad63f3a2a234f8f116f12efb1c8a8dce3aa17d2fad312ccc5f341/10_HowDoesTheBodyTakeShapeUnderPressure_QueerMuseum_Vienna_2022.jpg)

How does the body take shape under pressure?

Hosted by Queer Museum Vienna in partnership with Volkskundemuseum, How does the body take shape under pressure? brings together an international group of contemporary artists whose works are coming from the myriad experiences of pressure and questioning the dynamics of unproportional forces. Working between the lines of passive and defensive, social and intimate, pressure and pleasure; the exhibition presents artists’ allegorical positions to ponder upon political repression against queer&feminist existences. Curated by Alper Turan and Nazım Ünal Yılmaz, the exhibition, with the majority of the artists from Turkey, establishes an imaginary bridge between Vienna and Istanbul. The exhibition will take place between 18.05.2022 and 15.06.2022 at the Queer Museum Vienna in three rooms of the Volkskundemuseum, which have been made available to the QMV; a nomadic museum creating spaces for queer art, culture, and history as well as a queer future and futurity.

In the exhibition, we witness the bodies that are unbalanced, hanged, knocked down, cornered, pushed, and pressed against; we also see objects: forms of pleasure, protection, and of ferocity that are activated on flesh by pushing or protecting the corporal limits. Artists’ works in the exhibition are creating intimate scenes mimicking society’s mechanics, unfolding intertwined narratives, and posing primal and peripheral questions: How does political coercion manifest itself on a single body? How parallel run the power dynamics in our sexual practices to the societal ones? How does one transgress the pressure without pushing back? The bodies in the exhibition are in grip but they do not follow gestures of active resistance, assertive defense, or antagonism; instead, the bodies under pressure let themselves be pressed; are they submissively disobeying and taking pleasure or practicing and acknowledging helplessness?

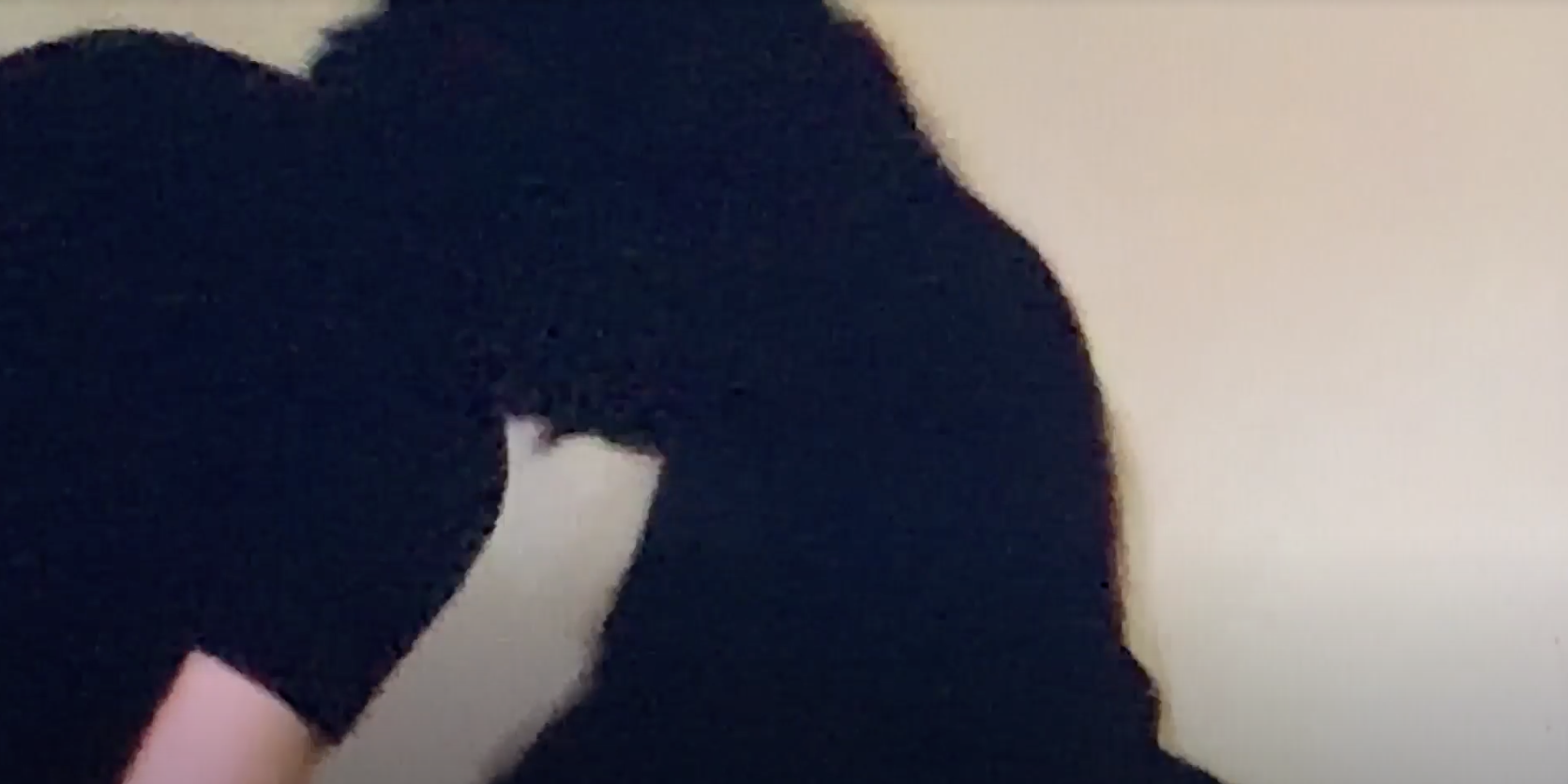

Dorian Sari, in their video work, A&a (If art fails, thought fails, justice fails) (2019), unveils a fight between two people opposed by dissimilar forces. While their nudity and bodily engagement create a certain eroticism, what we see is an inequality, oppression, and tyrannical torture that echoes social and racial realities. İz Öztat, in the video work Suspended (2019) made in collaboration with Ann Antidote, equates the suspension of freedom with becoming a body without willpower. Zeynep Kayan, in her video one one two, one two three: chair (2021), presents a scene where we see a figure that was pushed, pressed, and cornered against the wall by another silhouette as if one is chased by its shadow. Toni Schmale’s sculpture merges rigid, brutal, and industrial with sensual, libidinal, and unique; crystallizes the dialogue between sex and violence in the form of an oversized buttplug. Can Küçük in his sculpture, Centuries (2020), showcases a singularized subway handle as an orthopedic device for a body trying to stand in balance. In his Son (2020), Küçük creates knee pads, pink cushiony materials that are devised to protect the body from potential falls. Natalia Gurova showcases a sculptural silicon assemblage with a table, reproductions of Venus of Milo, and an artistic intervention to a statue from the Volkskunenmuseum collection. Venus, as one of the most copied forms of female beauty in Europe, becomes figurines in silicone that are bruised, still missing both arms, and barely standing upright. The table with a human arm hanging invitingly and pointing to the missing arms of Venus looks at the relationship between the body and the furniture. Artist also repairs the missing hands of the beggar figure from the 18th century which was borrowed from the folklore museum’s profane collection. The artist's intervention of attaching two silicon hands on top of show glass empowers the amputated beggar, suggesting a revision to the societal discipline of the precarious subject.

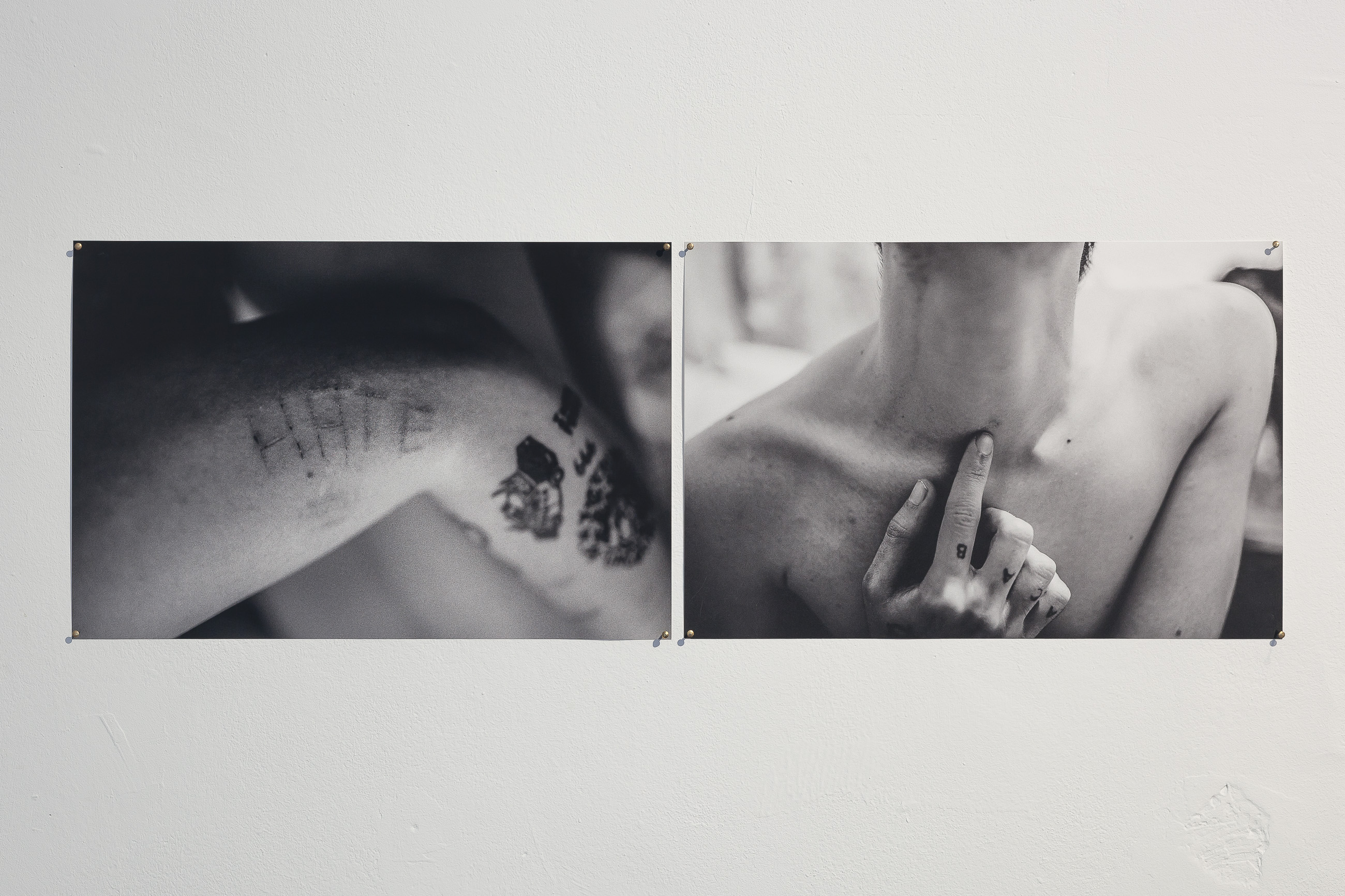

Cansu Yıldıran's three photographs describe three bodies with traces of violence in the form of cuts, tattoos, and wounds, questioning the sociality of the risks taken and wounds haven under personal responsibility. Carlos Vergara, in his installation, Untitled (Caribbean Dreams) (2021), self-exoticizes his Caribbean heritage and questions his home. He stacked a bundle of red monobloc chairs towered over a plastic palm tree evocating a pile of bodies fastened to each other and holed, run through, violated by phallic. Home and its destructive forces are pivotal in Nihat Karataşlı’s video, A Home to Dream of (2017) which documents the destruction of his other work, Home, a sculpture of palm trees in a lightbox. This act of documenting the destruction of the home creates a dream in itself, also suggesting the disfigurement and demolition that lead up to recreations.

How does the body shape under pressure? creates a space of reflections on negotiating the pressure within the intertwined structures of social, sexual, and political. The exhibition, within the setting of a folklore museum, suggests a queer critique of material culture and museum-making and questions how much violence and desire are being stored in the body and how much of a body can fit in a museum. The exhibition, commissioned by the Vienna Queer Museum, reminds us how oppression and violence are concealed in the glorification of queer existence in today's western politics, and how fascism establishes itself in the relationship between two people.

About Queer Museum Vienna: The Queer Museum Vienna (QMV) is an association and an open initiative that is in the process of exploring the requirements for a queer culture house and is now a guest at the Volkskundemuseum (Folklore Museum) of Vienna. The aim is to give an outlook on a projected, future house for queer cultural history and art in Vienna. Among other things, the main question is how queer artistic works, culture, and lifestyle relate to folklore and its museumization. Through exchange and discussion, its members want to find out what is expected of a queer museum and what it should be able to achieve. In this respect, the guest museum sees itself as a place for networking and as aplatform for queer activist projects, voices, and opinions. As a showcase, the museum pushes open the window into a queer future, futurity. At the same time, it celebrates the common history that has been brought into focus. A history marked by ostracism, exclusion, persecution, hiding and

shame, the individual and collective search for identity, and the attempt to locate oneself in the social fabric under perspectives such as legalization, equality, and pride.

In the exhibition, we witness the bodies that are unbalanced, hanged, knocked down, cornered, pushed, and pressed against; we also see objects: forms of pleasure, protection, and of ferocity that are activated on flesh by pushing or protecting the corporal limits. Artists’ works in the exhibition are creating intimate scenes mimicking society’s mechanics, unfolding intertwined narratives, and posing primal and peripheral questions: How does political coercion manifest itself on a single body? How parallel run the power dynamics in our sexual practices to the societal ones? How does one transgress the pressure without pushing back? The bodies in the exhibition are in grip but they do not follow gestures of active resistance, assertive defense, or antagonism; instead, the bodies under pressure let themselves be pressed; are they submissively disobeying and taking pleasure or practicing and acknowledging helplessness?

Dorian Sari, in their video work, A&a (If art fails, thought fails, justice fails) (2019), unveils a fight between two people opposed by dissimilar forces. While their nudity and bodily engagement create a certain eroticism, what we see is an inequality, oppression, and tyrannical torture that echoes social and racial realities. İz Öztat, in the video work Suspended (2019) made in collaboration with Ann Antidote, equates the suspension of freedom with becoming a body without willpower. Zeynep Kayan, in her video one one two, one two three: chair (2021), presents a scene where we see a figure that was pushed, pressed, and cornered against the wall by another silhouette as if one is chased by its shadow. Toni Schmale’s sculpture merges rigid, brutal, and industrial with sensual, libidinal, and unique; crystallizes the dialogue between sex and violence in the form of an oversized buttplug. Can Küçük in his sculpture, Centuries (2020), showcases a singularized subway handle as an orthopedic device for a body trying to stand in balance. In his Son (2020), Küçük creates knee pads, pink cushiony materials that are devised to protect the body from potential falls. Natalia Gurova showcases a sculptural silicon assemblage with a table, reproductions of Venus of Milo, and an artistic intervention to a statue from the Volkskunenmuseum collection. Venus, as one of the most copied forms of female beauty in Europe, becomes figurines in silicone that are bruised, still missing both arms, and barely standing upright. The table with a human arm hanging invitingly and pointing to the missing arms of Venus looks at the relationship between the body and the furniture. Artist also repairs the missing hands of the beggar figure from the 18th century which was borrowed from the folklore museum’s profane collection. The artist's intervention of attaching two silicon hands on top of show glass empowers the amputated beggar, suggesting a revision to the societal discipline of the precarious subject.

Cansu Yıldıran's three photographs describe three bodies with traces of violence in the form of cuts, tattoos, and wounds, questioning the sociality of the risks taken and wounds haven under personal responsibility. Carlos Vergara, in his installation, Untitled (Caribbean Dreams) (2021), self-exoticizes his Caribbean heritage and questions his home. He stacked a bundle of red monobloc chairs towered over a plastic palm tree evocating a pile of bodies fastened to each other and holed, run through, violated by phallic. Home and its destructive forces are pivotal in Nihat Karataşlı’s video, A Home to Dream of (2017) which documents the destruction of his other work, Home, a sculpture of palm trees in a lightbox. This act of documenting the destruction of the home creates a dream in itself, also suggesting the disfigurement and demolition that lead up to recreations.

How does the body shape under pressure? creates a space of reflections on negotiating the pressure within the intertwined structures of social, sexual, and political. The exhibition, within the setting of a folklore museum, suggests a queer critique of material culture and museum-making and questions how much violence and desire are being stored in the body and how much of a body can fit in a museum. The exhibition, commissioned by the Vienna Queer Museum, reminds us how oppression and violence are concealed in the glorification of queer existence in today's western politics, and how fascism establishes itself in the relationship between two people.

About Queer Museum Vienna: The Queer Museum Vienna (QMV) is an association and an open initiative that is in the process of exploring the requirements for a queer culture house and is now a guest at the Volkskundemuseum (Folklore Museum) of Vienna. The aim is to give an outlook on a projected, future house for queer cultural history and art in Vienna. Among other things, the main question is how queer artistic works, culture, and lifestyle relate to folklore and its museumization. Through exchange and discussion, its members want to find out what is expected of a queer museum and what it should be able to achieve. In this respect, the guest museum sees itself as a place for networking and as aplatform for queer activist projects, voices, and opinions. As a showcase, the museum pushes open the window into a queer future, futurity. At the same time, it celebrates the common history that has been brought into focus. A history marked by ostracism, exclusion, persecution, hiding and

shame, the individual and collective search for identity, and the attempt to locate oneself in the social fabric under perspectives such as legalization, equality, and pride.